Neurips 2025

Learnings from Neurips 2025

I attended NeurIPS from December 2 to December 6 in San Diego. The conference was amazing—so many great minds coming together in one place. I learned a lot and made valuable connections. I realized that If you want to become one of the leading researchers in your field, you should definitely attend all major conferences. It doesn’t matter whether your paper is accepted, whether you are presenting, or whether someone is sponsoring you. Save money or even borrow money—just attend. The return is extremely high: you will gain ideas, motivation, energy, and connections.

The main topic nowadays is scaling laws and how to optimize inference. We moved from scaling laws in pre-training toward scaling at test time (inference compute). I believe that people who can effectively optimize inference-time computation will be the real winners.

Below are some ideas and papers that I found interesting and wanted to write down so I wouldn’t forget them.

1. Language Model Training Dynamics

From my experience, when training large models across multiple nodes, every small nuance can have a huge impact. For example, training slightly longer during pre-training can sometimes lead to worse performance after fine-tuning on downstream tasks. This makes it extremely important to evaluate dozens of checkpoints regularly.

In this paper, the authors conducted extensive experiments and analysis of training dynamics across all phases of LLM training: pre-training, continued pre-training, supervised fine-tuning, and reinforcement learning.

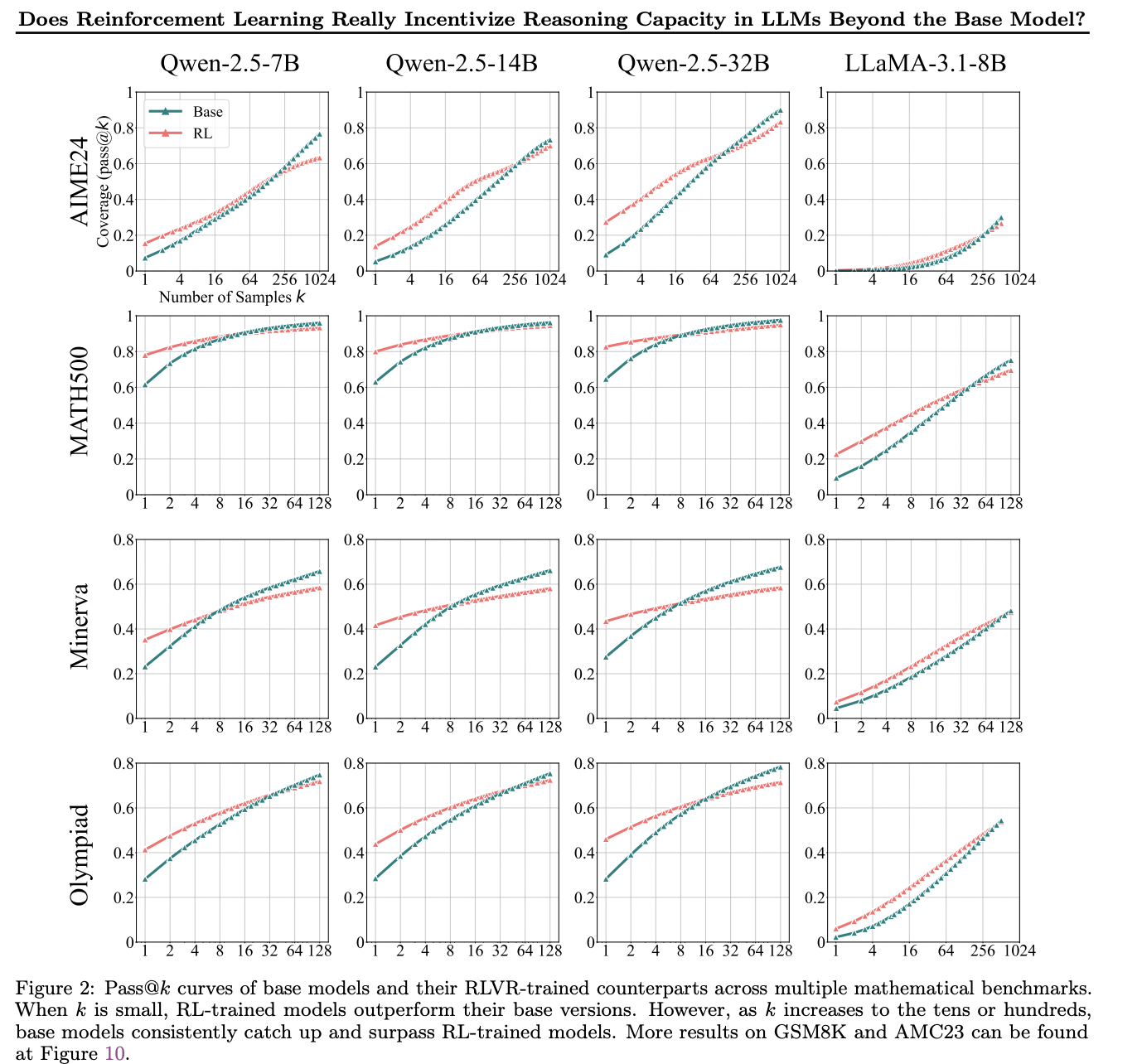

2. Does RL Really Incentivize Reasoning Capacity Beyond the Base Model?

The authors observed that RLVR does not teach the base model fundamentally new reasoning patterns; instead, it improves sampling efficiency toward correct paths. While RLVR-trained models outperform their base models at smaller values of k (e.g., k = 1), base models achieve higher pass@k scores when k is large.

I observed exactly the same behavior when experimenting with GRPO, my LinkedIn post about this.

3. Prompt Compression

Test-time compute is now being scaled aggressively. Context lengths can reach up to 100k tokens, which is often excessive. Several techniques aim to compress prompts.

One approach uses open-source models and small datasets to analyze which tokens are important in the prompt (e.g., via attention layers). Only those important tokens are then passed to a black-box model. This paper received a spotlight, but I couldn’t find it afterward.

4. Adaptive Reasoning Length

Another idea focuses on efficient test-time compute. The authors noticed that reasoning models often generate unnecessarily long chains of thought (CoT) for simple problems. They asked whether models could be made more adaptive—producing short CoTs for easy tasks and longer CoTs for harder ones.

While the idea is strong, it is difficult to implement in a general way. Their solution was to use a dataset where each task had a difficulty label. Using ChatGPT, they generated solutions conditioned on difficulty: short CoTs for easy problems and long CoTs for hard ones. They then fine-tuned an open-source model on this data.

5. Model Compression via Reduced Floating-Point Precision

This was a very interesting compression idea. In bfloat16, there is 1 sign bit, 8 exponent bits, and 7 bits of significand precision. The authors analyzed the weights of several popular open-source LLMs and plotted the distribution of used bits for both exponent and mantissa.

They found that, for the exponent, only 3–4 bits were actually used by the weights. Based on this, they proposed using an 11-bit floating-point format, saving more than 25% of memory.

During inference, the model is stored in this reduced format. For each layer, weights are temporarily converted to bfloat16 for matrix multiplication and then stored back in the compressed format. This approach does not degrade performance, saves ~25% memory, and incurs about a 5% slowdown. The idea could be applied to other models as well.

6. Tensor Products in Attention

“Tensor product in attention is all you need.” The authors represent Q, K, and V as:

Q = Σ a_q,i × b_q,iK = Σ a_k,i × b_k,iV = Σ a_v,i × b_v,i

Here, a and b are low-rank matrices. This is similar to low-rank decomposition, where large matrices are expressed as products of smaller ones, reducing memory usage and FLOPs. The authors even claim this approach improves performance.

7. Interpretability

There are three main directions in interpretability:

-

Attribution Problem

Given a trained model and an input, why did it produce a specific output?

Example: In credit scoring, why was a loan approved? Which features mattered—salary, gender, etc.? -

Data Attribution

How does a particular training data point influence the output? What happens if we modify or remove it? -

Component Attribution

Which components of the model contributed to a given output?

Most interpretability methods operate post-training. An open question is whether we can design models to be interpretable by construction while maintaining state-of-the-art performance. Some research explores adding interpretable modules directly into model architectures.

8. Benchmarks and Illusions of Progress

There was a great talk about benchmarks and whether they truly measure model capabilities. Ilya mentioned that models keep improving on benchmarks, but not necessarily in real-world use cases.

An analogy from the 19th century illustrates this. There was a horse that appeared to perform arithmetic: you would ask it to add numbers, and it would tap its hoof the correct number of times. A psychologist later blindfolded the horse, after which it could not answer a single question. The horse wasn’t doing math—it was picking up subtle human signals. While tapping, it watched the person and sensed when to stop.

This raises an important question: are our benchmarks truly testing intelligence, or are models just learning to exploit patterns in evaluation setups?

9. Rethinking AI Impact

Another insightful talk focused on how we conceptualize AI. When cars were first introduced, they were compared to horses: horses didn’t need oil, could navigate narrow streets, and seemed superior in many ways. Some early cars were even designed to resemble horses, with horse heads mounted on the front.

Over time, comparisons shifted from horses to cars themselves. Today, no one compares cars to horses anymore.

The question is: are our current ways of thinking about AI similarly constrained by human-centered assumptions? Perhaps AI will develop capabilities that are fundamentally different from ours—and we are not yet imagining them correctly.